Booze and Jews! Rags to riches! War! What else could you ask for in a story?

This story comes via a translation I just finished for a client. They had a copy of this newspaper article in the family, but lost it. They found it again recently online through a digitized database of Yiddish newspapers. All he knew about his great-great-grandfather was something about a ferry. I found this translation job to be quite intriguing. Enjoy the read!

Linguistically, the article is interesting for its use of Yiddish sarcasm (you have to catch it).

The Grodner Moment Express, November 23, 1928. online link

Yankel the Ferryman from Mosty Is Celebrated For His Help in the Polish-Bolshevik War

To Save a Polish Military Unit

(From our correspondent Lunner)

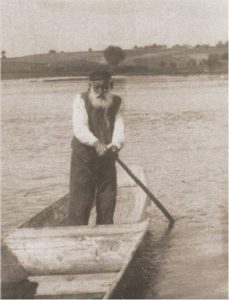

Kith and kin in Mosty know old Yankel Boyarsky; but if you go there and ask for him by his name, “Yankel Boyarsky,” barely anyone will be able to give an answer, because in Mosty almost everyone only knows him by the name “Yankel the ferryman”; a name he has earned after years of transporting passengers and drivers on a big wooden ferry over the Neman, which flows through many a town.

And something recently happened to this old “Yankel the ferryman” that is now a sensation in Mosty and in all the surrounding towns.

The story goes like this: In 1920, during the Polish-Bolshevik war, there was a bloody battle in Mosty between the Polish military and the Bolsheviks. The Polish soldiers, because they were being overtaken by the enemy, were forced to retreat, and one unit consisting of a captain and ten soldiers became separated from their regiment at night and stayed in Mosty; as the Bolsheviks were already very close, the Polish unit was only able to save itself by boating over to the other side of the Neman in order to regroup there with the other soldiers.

But how to get over to the other side when it is dark all around, you do not see a living soul (because all of the residents were hiding in their basements), and the ferry that is there does not have a rope so it is impossible to use.

The Polish unit knocked on a nearby house and knew that the only one who could come to their aid was old Yankel the ferryman. The soldiers went straight for him, and although shots could be heard from the Bolsheviks nearby, nevertheless old Yankel, risking his life, transported the Poles to the other side, and it turned out that they were saved from falling into the Bolsheviks’ hands.

It was 8 years since those events and the entire story had faded from old Yankel’s memory. We come to the events several weeks ago when a monument was set up in Mosty for all of those who had fallen there in the battles of 1920.

Many high-ranking military came to the ceremony, and the old ferryman ferried them over to the other side of the Neman.

When all of the officers got off the ferry, one of them stopped and started looking intently at old Yankel; then he went over to him, gave him a pat on the shoulder, and said:

“Remember how eight years ago you transported us over the Neman at night and because of that you saved us from the Bolsheviks? As soon as we come to the 10th anniversary of Poland’s independence, you deserve a reward, and I will truly see to it that you get one!”

Yankel, a real expert in Polish, nodded his head and the officer went to his friends. Several weeks went by when suddenly on the Sabbath, the 10th of November, on the eve of the anniversary of Poland’s liberation, Yankel Boyarsky received an official telegram inviting him to come to Warsaw immediately and contact the office of the War Ministry.

Old Yankel, who had understood very little of the officer’s speech or about what he wanted from him, ran, in shock, over to the rabbi asking for advice about what to do because never in his life had he gone farther than twenty kilometers outside of Mosty, so such a long trip was very daunting.

But when you ask for help, you get what you ask for — the rabbi felt sorry for the old man and agreed to accompany him to Warsaw.

Yankel put on his Sabbath frock, borrowed a new lamb fur coat from a good friend, polished his boots, packed his tallit and tefillin and left for his long trip, accompanied by cries from those at home who thought, “who knows what they will do with him there.”

But how great was the old man’s surprise when he saw the same officer at the War Ministry as before, and the officer asked him what sort of reward he wants for the assistance that he provided in a time of war to the Polish military unit.

Yankel stammered that he would be happy with anything that he would be willing to give, and the officer then gave him a a lifelong liquor permit without having to pay any taxes.

The old man did not believe his eyes and only when he went with the rabbi to a lawyer and he translated the permit to them, did he understand the fortune that he had come into.

Full of joy, Yankel came back home to Mosty, thanking the Lord for the great kindess that the noble Polish officer had shown him.

Motele Lunner

Contact me if you need a Yiddish newspaper article translated.